Phase 2: How do we perceive near-human faces?

For Phase 2, I set out to explore more about the uncanny valley effect by looking at it from the point of view of face perception. I had noticed in Study 2 that people seemed to be describing the uncanny faces in a different way to how they described the human and artificial faces, and I had a theory for why that might be. However, I’d only looked at five different faces in the Study 2, so it might have been that the differences were caused by those faces, rather than representing something general about near-human, human and artificial faces. A more systematic approach was needed.

When we look at faces, they are generally perceived ‘holistically’ as a single impression of the person rather than as a collection of the individual features that make up their face. Following on from my first phase, my theory was that the near-human faces were unusual as they were actually being processed in this feature-by-feature way, and in particular, that people were concentrating on the eyes of the near-human faces more than they were concentrating on the eyes of the human or artificial faces. Of course, thinking back to the images used in the first phase, the three near-human images did have distinctive eyes, so this needed careful testing to find out what was actually going on.

New research images

I needed a new set of images for this next study. I wanted to make sure that I carefully controlled how close to human each one was, and decided to do this by morphing from a non-human image through to a matched picture of a human, as shown below.

I was also interested in whether I would find an uncanny valley effect just for robots, or if one would appear when animals, dolls or statues were morphed into humans, so I created four types of morphs to see whether a valley effect would emerge. Here are examples of the starting images I used for animals, dolls, robots and statues.

I create a series of short films which morphed between the different types of artificial and human images and took stills at the 0%, 25%, 50%, 75% and 100% human points. In total, this gave me 60 different images to test.

How eerie were my morphed faces?

I wanted to be able to link any findings about how the faces were perceived to whether they were actually uncanny so my first task was to collect ratings from people who would not be involved in the face perception experiment. The rating study was carried out online, and was live throughout August 2011, and 107 people took part in that time. 68% of those were female and the average age was 38. 80% said they were located in the United Kingdom. Ratings were collected for how strange, human-like and eerie the faces seemed.

The chart below shows the average eeriness ratings given for the different types of faces, at each stage in the morph from non-human to human.

If you compare this chart to the 'classic' uncanny valley graph, you would expect that the eeriest faces would be those at the 75% point. However, this was not what I found: my faces were eeriest at the 50% point. You can also see that the morphs for the four types of face did indeed have different patterns of eeriness, but none were close to what would have been expected of an uncanny valley.

Are near-human faces processed holistically rather than analytically?

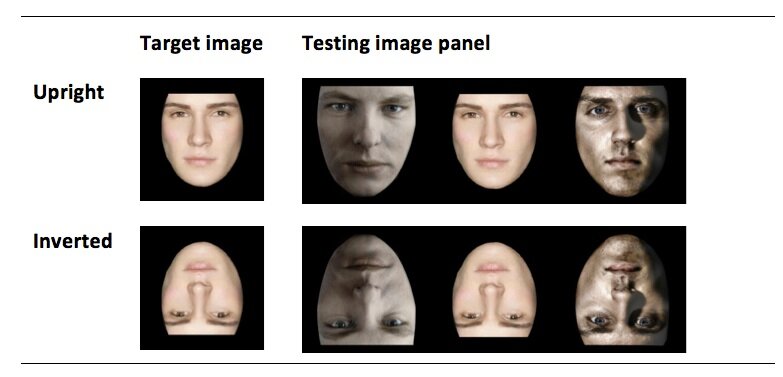

My second study in Phase 2 was an experiment using the morphed faces that have been described above. Psychologists have previously found that faces are harder to recognise when they are turned upside-down. By inverting the face, you change its overall appearance even though the individual features are the same, and this difficulty in recognising inverted faces has been explained as being due to a disruption to the mechanism of holistic perception that allows us to recognise faces quickly and easily. This face inversion effect means that people are reliably slower at recognising faces when they have been turned upside down, so I could design an experiment to see what happened to recognition speed when near-human faces were inverted.

My theory was that the near-human faces were being processed differently, in terms of individual features rather than the whole face, perhaps because their distinctive and unusual eyes prompted more analytic processing. When a face is turned upside down, we lose the sense of the overall face and so have to look at individual features for clues to recognise it, so if people were already paying attention to the eyes in the near-human faces, I thought that this might mean that those faces would not be as badly affected by inversion, and people would be able to identify them faster than the human or artificial faces.

The experiment was carried out face-to-face during November and December 2011. 54 people took part, 65% of the participants were female and the mean age was 43 years old. Participants were shown one face at a time, and asked to remember it. Sometimes they were presented upright, and sometimes upside down. They were then asked to pick out the face from a set of three, like this:

I measured how quickly participants identified each face, and analysed the results. I had expected to find that the artificial and near-human faces would take longest to recognise when they were inverted, and the near-human faces would all be faster. I wanted to look at whether the animal, doll, robot or statue versions had different patterns, but hadn’t predicted the nature of that difference. What I actually found was quite different from what I had expected:

What next?

This study had found an interesting pattern of differences in processing speed for faces that varied in human-likeness, but one additional aspect of the uncanny valley effect remained to be explored: that of emotional responses to near-human faces. The final research phase looked at this in detail.